When the Commodore Amiga was released in 1985, it marked a turning point in personal computing. Designed with custom chips for graphics and sound, the Amiga offered creative possibilities that far exceeded those of most home computers at the time. While it never achieved mass-market dominance in the United States, it quickly gained a devoted following in Europe and the UK, where artists, designers, musicians, and programmers embraced it as a flexible, experimental tool.

As a site of practice, the Amiga fostered informal networks of users who exchanged software, techniques, and ideas, often outside institutional or commercial frameworks. In retrospect, many artworks created on the Amiga sit at the threshold of the digital age, anticipating later developments in animation, interactive art, net art, and media installation. Yet despite its influence, Amiga-based art remains unevenly documented, poorly categorised, and at risk of disappearing.

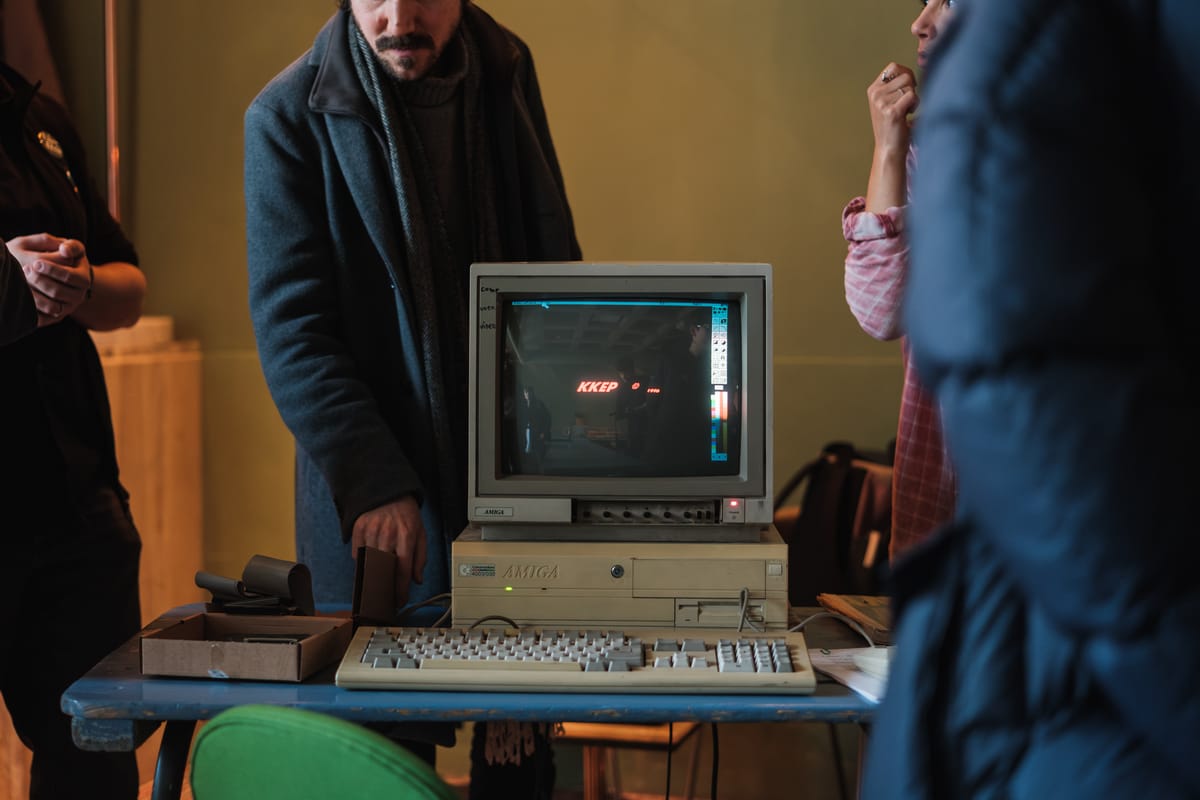

That risk intensified after Commodore’s bankruptcy in 1994. As the hardware and storage media aged, access to Amiga artworks became increasingly difficult. Today, the challenge is not only technical but also historical: how to recognise, describe, and care for works made with a platform that has slipped out of mainstream technological memory.

Technical foundations and aesthetics of Amiga artworks

The Amiga stood out for its tight coupling of hardware and software built specifically for real-time audiovisual work. Its custom chips supported smooth animation, layered graphics, and synchronised sound at a time when most personal computers struggled with static images. Tools like Deluxe Paint, ProPaint, and GraphiCraft let artists work frame by frame, merging drawing, animation, and timing into a single workflow that directly shaped the visual language of early digital art.

Those technical constraints also produced a recognisable aesthetic. Restricted colour palettes, visible pixels, low resolutions, and looping animations became expressive choices rather than flaws. Artists learned to work with the machine’s boundaries, often embracing abstraction, repetition, and modular composition. The result was a body of work that is shaped as much by experimentation as by necessity and technological limitations.

AMIGA NU: Mapping a scene, filling the gaps

Initiated by LI-MA in 2024, the AMIGA NU project set out to better understand this history by focusing on the Dutch Amiga scene of the 1980s and 1990s. Through archival research, interviews, and hands-on technical investigation, the project identified artists and works that had largely fallen outside existing collections and narratives.

Rather than treating the Amiga as a footnote in computer history, the project approached it as a cultural ecosystem. This meant looking not only at individual artworks, but also at the networks, tools, and working methods that surrounded them. In doing so, the research revealed significant gaps in how Amiga-based works are represented in institutional collections, particularly the underrepresentation of women artists working with the platform.

A central aim of the project, which was funded by Cultuurfonds and led by Junior Conservator Olivia Brum under the supervision of LI-MA Director Gaby Wijers, was to develop clearer ways of identifying and describing Amiga artworks. Many collections still rely on broad labels such as “computer-based art”, which obscure the specific technological and cultural contexts in which works were produced. By refining how these works are categorised, they become easier to recognise, identify, research, and preserve.

Notable Amiga artists and artworks

Identifying a single “definitive” Amiga artwork is difficult. As Olivia Brum notes, the AMIGA NU project uncovered a wide range of compelling works, each revealing different aspects of the platform’s artistic potential. The research began with the Amiga works of Colombia-born artist Raul Marroquin, a pioneer of video and media art known for his playful critiques of consumer and media culture. Marroquin developed several important works using the Amiga and Deluxe Paint, yet many of his floppy disks had not been accessed for over thirty years prior to the project. Through disk imaging and emulation, these works could be recovered and studied again.

One particularly illustrative example is the animation Eureka (1986). Created using Deluxe Paint, one of the most widely used Amiga programs, Eureka demonstrates several defining characteristics of Amiga aesthetics. The animation uses a highly restricted colour palette – just four colours: yellow, black, blue, and white – alongside low resolution and visible pixelation. While the Amiga could support up to 64 colours depending on memory and resolution, such constraints were often embraced creatively, shaping the visual language of the work rather than limiting it.

The Amiga also attracted artists already established in other media. At the launch of Commodore’s family computer series, Andy Warhol famously used ProPaint to create a live digital portrait of Debbie Harry at Lincoln Center. He later produced Amiga-based drawings using GraphiCraft, including reinterpretations of the Campbell’s soup can and The Birth of Venus. Keith Haring likewise experimented with Amiga computers in the late 1980s, producing digital works that remained stored on floppy disks for decades.

Through the AMIGA NU project, LI-MA mapped the Dutch Amiga scene of the 1980s and 90s, tracing networks of artists whose works are still underrepresented in collections. This research identified key Amiga-based artworks not yet held by LI-MA but crucial for understanding the platform’s role in early computer art. The project also brought greater visibility to women artists working with Amiga, a group that remains disproportionately absent from many media art collections.

Other artists encountered during the project demonstrate the diversity of Amiga-based practices. Dutch performance artist Annie Abrahams integrated Amiga software into physical installations, combining digital animation with performative and spatial elements. The collective RxAxLxF used interactive digital video and algorithmic systems to examine mechanisms of classification and control. Graphic designer Max Kisman employed the Amiga across print, television, and animation, blending analogue cut-out aesthetics with digital production. Petra de Nijs (also known as LuxxX) produced Amiga animations both independently and collaboratively, offering a vital perspective on early digital animation practices.

Together, these works show that the Amiga was not associated with a single genre or style, but functioned as a flexible platform adapted to many artistic intentions.

Who cares for Amiga?

As Amiga artworks age, they face multiple risks. Within art history, they remain under-researched, meaning many works go unrecognised or are loosely categorised as “computer-based art”, a label that obscures their specific technological and cultural context. This lack of precision complicates identification, documentation, and preservation within archives and collections.

The material fragility of Amiga storage media adds another layer of urgency. Floppy disks were central to both software distribution and artwork storage, yet they are now highly vulnerable to degradation. Without timely intervention, the data they contain may be permanently lost. Accurately identifying Amiga-based works is therefore essential. The goal is not simply categorisation, but recognition: being able to identify Amiga works within larger collections, understand how they were made, and infer how they were originally presented. Even when files have been migrated, knowing their Amiga origins provides insight into essential artistic intent and technical context.

Because media artworks rely on rapidly obsolete hardware, preservation often depends on emulation. Unlike migration, emulation does not alter the original digital object, but recreates the software environment needed to access it. This approach has become a standard strategy among archives, museums, and libraries dealing with early digital art that can no longer be accessed using contemporary systems.

In the Netherlands, LI-MA supports this legacy by providing access to Amiga hardware and emulated environments, fostering a collaborative space where artists and heritage professionals can view, study, and care for Amiga-based works. With continued support from the Dutch Digital Heritage Network (Netwerk Digitaal Erfgoed), these facilities are being expanded to improve accessibility and long-term preservation.

The history of Amiga art is still being written, with many works remaining undocumented. Addressing this gap requires developing shared vocabularies, technical knowledge, and a willingness to treat early digital art as a legitimate form of cultural heritage that deserves proper stewardship and care. Those interested in Amiga art, its rich history, or how to preserve it are encouraged to reach out to LI-MA and contribute to the growing network of knowledge around this remarkable platform.