Reviews

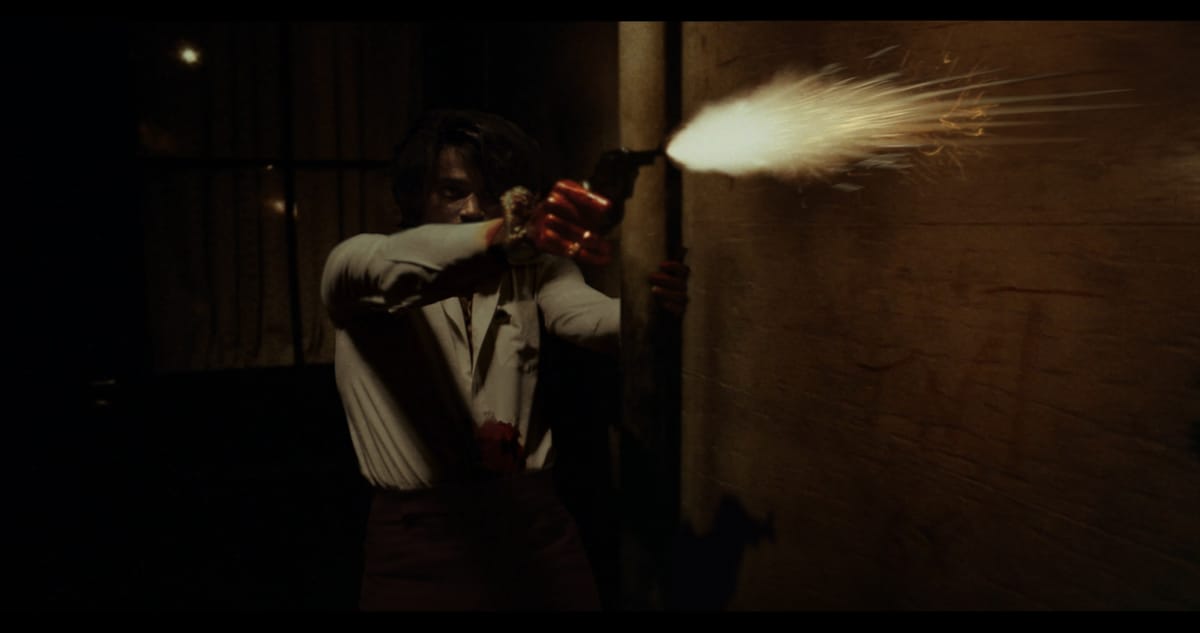

It takes a special artist to be given two solo exhibitions running concurrently at two different spaces in New York City. Add to that the lofty distinction of holding a Venice Golden Lion, in part for profoundly shifting the culture of the contemporary moving image. Credit these accomplishments to the man that they call AJ – better known as Arthur Jafa.

This post is for subscribers only

Subscribe now and have access to all our stories, enjoy exclusive content and stay up to date with constant updates.