Reviews

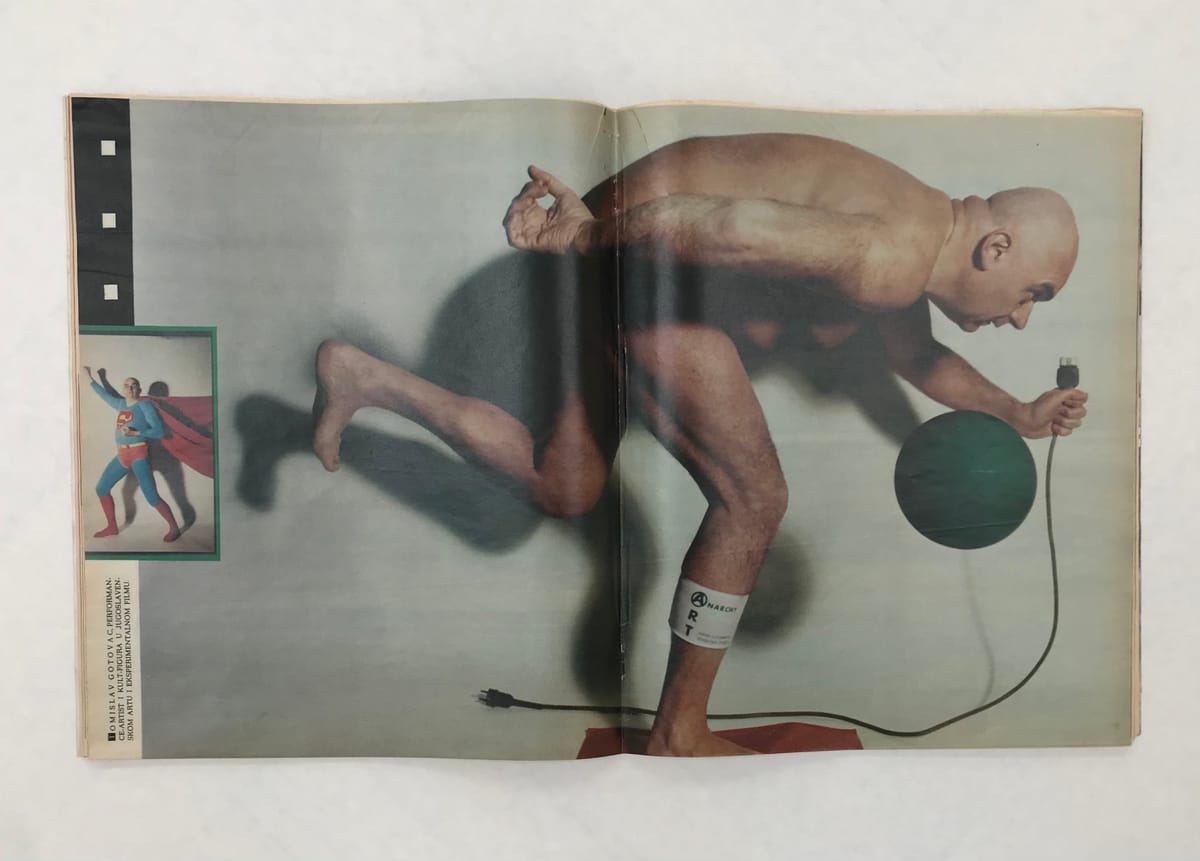

It’s not easy to work in Paris, as it is in Rome, for instance, or Madrid, or Zagreb, which is heaven. You didn’t even need special police permission for the streets. You just go out and ask people to move aside... The whole town is like a back lot. – Orson Welles

Zagreb is the place with the sun – and the planets. Unique in the world, the Croatian capital encompasses within its boundaries a colossal scale model of the solar system. Ivan Kožarić installed Prizemljeno sunce (The Grounded Sun) in 1971; Davor Preis completed the job with Devet pogleda (Nine Views) in 2004, placing metallic spheres representing nine planets (including Pluto) of appropriate sizes and at appropriate distances relative to the sun. To navigate this city is thus, in conceptual terms, to wander freely beyond the Earth’s gravitational pull.

This post is for subscribers only

Subscribe now and have access to all our stories, enjoy exclusive content and stay up to date with constant updates.